Key discoveries

Balearic Lighthouses

-

Mallorca

-

Cabrera

-

Sa Dragonera

-

Formentera

-

Menorca

-

Eivissa

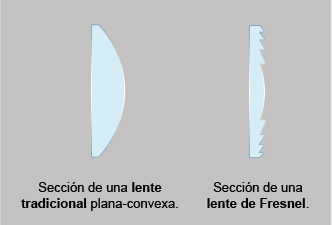

FRESNEL

The French physicist Augustin Fresnel is one of the most significant figures in the field of lighthouse technology due to the fact that he was responsible for the introduction of his optical systems to lighthouses and beacons all over the world.

The first lighthouse to be equipped with this type of optic was at Corduan in France in 1823. Given its success, it was gradually progressively introduced in many other lighthouses as the most effective way to improve light range.

Fresnel’s design meant that lens size could be significantly reduced at the same time as range was increased.

STATIONARY OPTICS FOR 6th ORDER LIGHTHOUSES

The optics acquired by the Spanish Government during the second half of the 19th Century were mainly built by three French companies, Lepaute, Sautter and Barbier & Benard (later BBT). After this, at the beginning of the 20th Century, German optical equipment, manufactured by Julius Pintsch was also employed. However from the 1920s, the Swedish company AGA, founded by the inventor Gustav Dalen became the market leader.

In the Balearic Islands, the lighthouses with the greatest ranges built as part of the 1847 plan were of the 2nd Order. Some of their optics are now on display at the Portopí exhibition. However the great majority were of the 6th Order, such as the lighthouses at Cala figuera, Maó, Botafoc, Cap Blanc, Cap Salines, Sa Creu, Alcanada and Portocolom.

The optical equipment employed at these lighthouses used a lens with a diameter of 30cm with a dioptric central section and two upper and lower sections consisting of a varying number of catadioptric rings.

As a consequence of the new 1902 Plan, new rotating mechanisms consisting of clockwork machinery and a mercury flotation tank were introduced. The first lighthouse in the Islands to be equipped with this technology was that at Punta de l’Avançada in 1905. In the remaining lighthouses, this process took place in two different stages. In the second decade of the 20th Century and especially in 1917, 6th Order lighthouses were equipped with systems consisting of rotating screens that eliminated the old stationary light pattern for, in most cases, a system of light with occultations.

Later on, in the 1930s, and especially in 1928, many of the old 2nd Order lenses were adapted to the new rotating systems with mercury flotation tanks.

OPTIC FROM THE ILLA DE L’AIRE LIGHTHOUSE

This 2nd Order optic was built by the French company Sautter and started working at the L’Illa de l’Aire Lighthouse in Menorca on the 15th August 1860. It is similar to other rotating optics provided or in the first Plan and therefore includes a system of galets (small metallic wheels that supported the lens) for the rotation of the apparatus. The optic produced a light pattern of isolated flashes every minute using a Legrand lamp equipped with pistons.

It saw continuous service until 1965, being the last lighthouse in the Balearic Islands to use this system.

OPTICS FROM THE TRAMUNTANA (DRAGONERA) AND PORTOCOLOM LIGHTHOUSES

This optic was originally installed 1910 at the Tramuntana lighthouse, working through a system of weights and employing a single wick Maris lamp. However, after automation in 1960 using new Dalen solar valve systems, the optic was dismantled and then installed at Porto Colom lighthouse in 1965 when the system there was converted to run on electricity. At both lighthouses it emitted a light pattern consisting of two white flashes every ten seconds.

OPTIC FROM THE CAP LLEBEIG LIGHTHOUSE

This is one of the most singular optics on display at the exhibition, not only for its spectacular design, but also for the way it was transported from Dragonera Island to Portopí lighthouse.

It started working at Llebeig Lighthouse in 1910, emitting a light signal consisting of isolated flashes every seven seconds. In 1969 it was dismantled and taken out of service, being replaced by a “universal apparatus” (provisional lighting equipment) until the new automatic Dalen system was installed in the summer of 1971.

In 1980 the difficulties caused by the considerable weight of the base meant the help of the US Navy’s 6th Fleet was requested and the optic was finally transported by helicopter to the site of the future exhibition at Portopí.

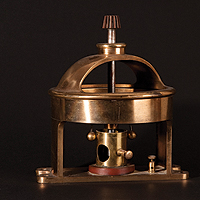

EARLY ROTATION MACHINERY

The 1847 Plan included weight-driven clockwork mechanisms that turned the whole optic or a part of it, with a stationary lower catadioptric area remaining fixed.

The possibility of rotating external vertical lenses with the main lens remaining stationary was also taken into consideration. In any case, the light patterns attained by these early rotation systems produced rather long-lasting rhythmical patterns.

SPEED REGULATORS

Two more characteristic of these early rotation systems were the use of galets (small metallic wheels) and the use of flanged speed regulators. Neither should it be forgotten that the weights employed for the rotation of early optical equipment were suspended from a hemp rope (as was the case of Na Pòpia Lighthouse) or an iron chain (at N’Ensiola Lighthouse) and it was not until the beginning of the 20th Century that steel cables and friction-based speed regulators were first introduced.

MERCURY FLOTATION TANKS

With the intention of eliminating the second disadvantage of early rotating optical systems (a long separation between flashes), many of the old catadioptric lenses were adapted to float in tanks of mercury, reducing friction and increasing the speed of optic rotation, to shorten the time between flashes.

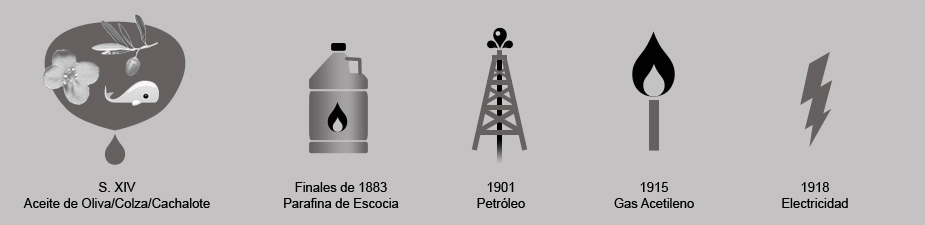

OLIVE OIL

Although in Ancient times lighthouses were illuminated using wood or coal fires, by the 14th Century, the lighthouse at Portopí was already equipped with a lantern with glass panes and wooden frames in order to protect a light produced by twelve olive-oil burning lamps (sixteen by the 16th Century). In the same way, Spanish lighthouses built in the mid-19th Century also olive oil, it being an abundant raw material. In France rapeseed oil was used and in England spermaceti oil.

At that time the oil was transported to many of the lighthouses by boat, even to those such as Cap Blanc and Cap Salines that were not situated on islands. Later on, these form of supply was limited to the more isolated lighthouses.

PARAFFIN

In the Balearic Islands changes in the use of fuel took place somewhat later than in Northern Spain. For example the changeover from olive oil to paraffin took place at the end of 1883 whereas at the lighthouse at Cabo Mayor in Cantabria had been converted in 1877. Although it may seem contradictory, the use of this imported fuel actually reduced the cost of marine lighting by 30% due to lower consumption.

Early problems consisting of frequent explosions in the lamps and the emission of noxious odours, both of which were caused by defective combustion, were cleared up by the use of Dotty lighters, so called after their inventor, an American sea-captain, who had come up with the idea in 1868.

PETROL

In 1901 petrol was introduced into most of the lighthouses in the Islands and as a consequence incandescent lamps were gradually introduced that did not use wicks but rather mantle burners impregnated with collodion (a cellulose nitrate that enhanced the burners’performance).

The most commonly used lighting system in the lighthouses in the Balearic Islands was that manufactured by the Chance Brothers in Birmingham, England. Chance lamps were classified by the diameter of the mantle burner into three categories: 85mm, 55mm and 35mm.

The first lighthouse to use this system was that at Llebeig in 1910. The system used two tanks, one for the petrol and the other for pressurised air to pump the fuel up to the lamp. Fuel consumption was much greater than that required by wick-burners but range was much greater.

ACETYLENE GAS

In 1912, the Swedish inventor Gustav Dalen was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics for the combination of automatic regulators and gas accumulators employed in the illumination of lighthouses and buoys. These new devices meant that lighthouses and other marine navigational aids could now be automated with the consequence that the lighthouse keepers and their families who had been obliged to live on small islands in conditions of extreme isolation could gradually abandon these postings for destinations with more comfortable living conditions.

Dalen founded AGA that took over from the French companies Sautter, Lepaute and Barbier,Bernard & Turenne as market leader in the supply of rotating optical systems for lighthouses and beacons. From now on automated switching on and off of lighthouses and beacons became a priority for government. The key to this automation was the solar valve. The first automated acetylene gas signals in the Islands were at Dau Gros in Ibiza and the buoys of the Port of Maó in 1917. The last systems to use this mechanism in the Archipelago were retired from service in 1995.

ELECTRICITY

After the first lighthouse in Spain to run on electricity was opened in 1888 at Cabo Villano in Galicia, this source of power became gradually more important in the field of marine navigational aids.

The first lighthouses to run on electricity in the Balearic Island were those at Botafoc in the Port of Eivissa, Cap Gros and La Creu at the Port of Sóller, Ciutadella and Maó in Menorca, as well as Portopí and La Riba at the Port of Palma, all of them electrified in 1918.

From then on, sooner or later all lighthouses and beacons have adopted the use of electricity in one form or another. At first electrical filament lamps were used along with automated lamp-changing devices, back-up generators and orbital timers for turning the lamp on and off. However many lights were converted directly from acetylene gas to solar power with the use of solar panels for the generation of electrical energy.

REMOTE CONTROL

At the end of the 1980 and especially in the 1990s, electricity gave way to electronics and finally to computers. A the present moment, the most important lighthouses controlled by the Balearic Islands Port Authority have all been integrated in the network of remote controlled signals.

This system means that lighthouses are now under continued vigilance through computer systems that communicate with the remote control centre via radio-modem, mobile telephone or land line. This technology allows commands to be sent to the lighthouse ordering it to be turned on or off, system checks, etc.